Fr Des was far-sighted. He tuned in to how a particular use of words can influence how people think about a political conflict. He realised that how a conflict is described and understood governs how people feel and react. In Springhill Community House during the conflict, he was forever encouraging his Ballymurphy neighbours to recognise their ingenuity and resilience in the face of brutal oppression.

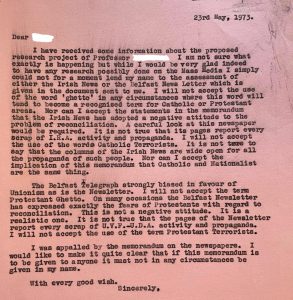

All this is clear in a letter of his from archive dated the 23rd of May 1973. He responds to a memorandum he received about a new research project that planned to investigate media coverage of the conflict. The memorandum is seeking his support.

To begin with, Des welcomes research into media coverage of the conflict. But, in this case, the welcome ends there. His response to the writer’s invitation is a point-blank refusal, ‘I simply could not for a moment lend my name [to this study].’ For one thing, he says the memorandum’s use of the word ‘ghetto’ as a shorthand reference to Catholic and Protestant areas is unacceptable, ‘in any circumstances.’ Nor can he accept references to, ‘Catholic Terrorists’ or to ‘Protestant Terrorists.’ He refutes the implication that ‘Catholic’ and ‘Nationalist’ are one and the same thing.

As for the memorandum’s assessment of the Irish News and Newsletter, he is equally forceful. ‘It is not true’, he writes, that the Irish News reports ‘every scrap of I.R.A. activity and propaganda’. Neither is it true that the Newsletter reports ‘every scrap of U.V.F. – U.D.A. activity and propaganda’.

Des’ letter closes by saying he is ‘appalled’ by what he has read. He restates, ‘I would like to make it quite clear that if this memorandum is to be given to anyone it must not in any circumstances be given in my name’.

He wrote this letter in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday (1972), after losing two brother priests, Fr Mullan in the Ballymurphy Massacre (1971) and Fr Fitzpatrick in the Springhill massacre (1972). All of those who lost their lives in these massacres were shot dead by the British Army. Media reports of these events, however, repeated an army briefing that blamed the dead for the carnage.

Des’s letter reveals how the language used in the memorandum reinforces a powerful state sponsored narrative that characterised the conflict as a violent sectarian battle between Catholics and Protestants from ghettos. It’s fair to say that Des was furious. Maybe one day we’ll come across the original memorandum in the archive. It might be useful to know if the research ever happened.

We can imagine his response to the nightly news on Gaza and Lebanon and to the silence on conflicts in Africa and elsewhere, ‘not in my name.’